This is a fantastic and insightful piece; it allows the reader to better understand the mind of Gordon Murray and see what influence the NSX had on the design of the McLaren F1.

To this day, the NSX is still a car that is near and dear to my heart. I put 75,000 Km on my NSX over the course of six or seven years.

It’s very difficult to discuss the NSX using current values and sensibilities. When the NSX debuted, the word “supercar” was still a relatively new idea in Europe. There are some who would say the Lamborghini Miura from the late 1960s was the first supercar. However, the truth is the explosion of modern supercars really started at the end of the 1980s.

At the end of the 80s was the time when McLaren Cars was conceiving the idea for the McLaren F1. To that end, I was concentrating on coming up with what I wanted in a road car.

To my thinking, the ideal car is one in which I could get in the driver’s seat and be out for a drive in downtown London and then want to continue straight on to the South of France. A car that you can trust, with functional air conditioning and retains daily drivability. No offset pedals allowed. No high dashboards restricting your view either. Having a low roof hitting your head every time you go over a bump in the name of aerodynamics and styling is out of the question. It is essential that a supercar be a pleasure to drive, and anything detracting from that must be excised.

I started by driving the cars known then as “supercars.” The Porsche 959, Bugatti EB110, Ferrari F40, Jaguar XJ220. Unfortunately, none of these fit the pattern of the supercar we were trying to build. What we wanted was a relatively compact, usable driver’s car. The Porsche 911 had the usability, but with the engine packed in the back, it had a weakness in its handling stability.

During this time, we were able to visit with Ayrton Senna (the late F1 Champion) Honda’s Tochigi Research Center. The visit related to the fact that at the time, McLaren’s F1 Grand Prix cars were using Honda engines.

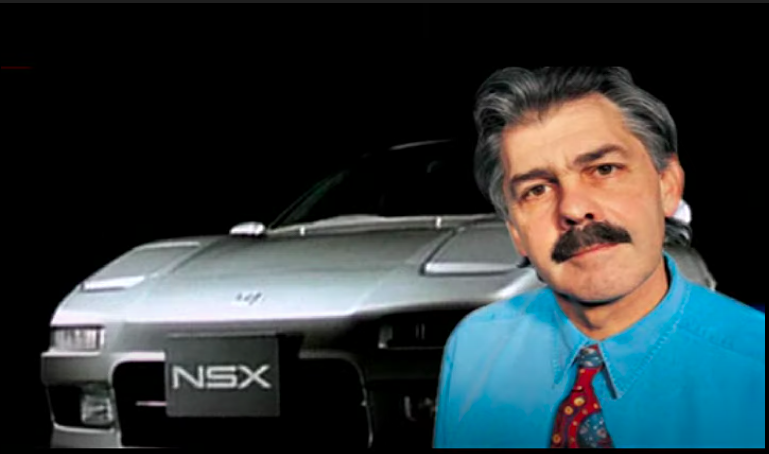

Coincidentally, I spotted an NSX prototype parked near the course. I also learned at the time that Ayrton was assisting in the development of the NSX and that Honda rear mid-engined sports car–the NSX–was the friendly supercar that we had been looking for. This car had perfectly functional air conditioning, a reasonably roomy trunk and of course, it was a Honda, with the high levels of quality and reliability that implies.

Then I had the opportunity to drive it. Along with Ron Dennis (President, McLaren Cars) and Mansour Ojjeh (Tag McLaren Group Representative), we drove the prototype on the Tochigi Research Center test course. I remember being moved, thinking, “It is remarkable how our vision comes through in this car.”

Of course as you know, the engine has only six cylinders; however, the NSX’s very rigid chassis is excellent and would easily be capable of handling more power. Although it’s true I had thought it would have been better to put a larger engine, the moment I drove the “little” NSX, all the benchmark cars–Ferrari, Porsche, Lamborghini–I had been using as references in the development of my car vanished from my mind. Of course the car we would create, the McLaren F1, needed to be faster than the NSX, but the NSX’s ride quality and handling would become our new design target.

When working on the development of a new car for years, it’s easy to be caught in certain pitfalls. When you drive the car under development for testing every day (in truth, I was responsible for two-thirds of the testing for the McLaren F1), in that time, you can unknowingly convince yourself you are making progress when in fact you are not. For example, it’s human nature that at the end of a long day you may want to think that your efforts to reduce low speed harshness are working better than they are. It is at times like this when you need a car to compare with. In those situations, the NSX time and again showed us the path in the areas of ride quality and handling, and also helped us recognize when we weren’t making as much progress as we thought.

In my opinion, the NSX’s most special quality has long been overlooked.

That could be summarized with the words, “The NSX’s suspension is amazing.”

Both the body and suspension are aluminum, and it probably couldn’t be helped that journalists’ attention has been focused on praising the aluminum body. However, the suspension is the much more impressive use of aluminum.

It’s lightweight, tough, yet compliant. Also contributing to the refined NSX’s handling and ride quality are 17 inch wheels and tires that are not overly large. The NSX’s suspension is truly an ingenious system, and back then I imagined the development costs must have been enormous. To achieve that unparalleled accuracy and superior ride quality, longitudinal wheel movement is allowed via the use of a compliance pivot.

Compliance refers to when you travel over a bump, the tire experiences a longitudinal force, which the tire and suspension must move with and absorb the shock. The pivot couples the upper and lower arms. It is connected to the arms via ball joints so that they move as a unit. When encountering input, the pivot rotates, keeping alignment changes to near zero while retaining compliance (see diagram). The inspiration obtained from this NSX suspension system would later influence the development of the McLaren F1′s suspension.

The NSX was also the first car to use DBW (Drive By Wire). It felt very pleasing. DBW is when instead of using a mechanical cable, an electronic signal is used to communicate throttle position. It achieved a very natural, linear feeling throttle, and I can now hide my embarrassment and confess that I copied the idea during the development of the McLaren F1 (laughs).

The low-slung NSX’s driver’s seat position also provided just the right head clearance and an amazing field of view. The NSX development team moved the air conditioning unit away from the dash and deep into the NSX’s nose in order to obtain more space. That air conditioning unit is an excellent one, and normally, you don’t notice whether it’s on or not.

On the day I bought the NSX, I pressed the “Auto” button and since then until selling it, I never had to touch it. It was that perfect. Ah, I also remember the audio system as being very good.

However, the media wrote up the aluminum body and the many merits and advantages I perceived in the NSX have largely been overlooked.

In my opinion, the NSX, while being such a great sports car, had two large flaws in its marketing. First, at the time, the public was not ready to accept a Japanese car that was this expensive. The second is that for supercar customers, the power figures were not quite high enough. Of course, the prototype’s engine was not bad, and soon the VTEC engine was added. Whenever I hear that VTEC sound it’s amazing. I am repeating myself, but the NSX’s excellent chassis would have been capable of handling much more power.

With just a slightly lower price, or possibly selling it with a different brand name and a different badge, or perhaps endowing it with a touch flashier and more aggressive styling and additional power, there is no question the NSX would have reigned as a cult star of the supercars.

During the development process of the NSX, racing drivers were invited to drive the car and give their thoughts. Three-time F1 champion Ayrton Senna was one of them. The NSX endured a month-long test at Suzuka circuit, and while Senna was testing the new Honda F1 car, he was asked to drive the NSX as well.

“I’m not sure I can really give you appropriate advice on a mass-production car, but I feel it’s a little fragile,” is what Senna apparently related to Honda engineers. Because of what he said, and through more testing at the Nurburgring, Honda made the chassis 50-percent stiffer.

“I’m not sure I can really give you appropriate advice on a mass-production car, but I feel it’s a little fragile,” is what Senna apparently related to Honda engineers. Because of what he said, and through more testing at the Nurburgring, Honda made the chassis 50-percent stiffer.